In the heart of the Middle Ages, a new conception of time began to take shape, transitioning from the fleeting shadows of canonical hours to the brilliant innovations of clock mechanisms. Originally, the day was punctuated by monastic prayers: Matins in the stillness of the night, Lauds at dawn, following the solar rhythm with Prime at 6:00 AM, Terce at 9:00 AM, Sext at noon, None at 3:00 PM, Vespers at sunset, and Compline before nightly rest. This division defined the essence of daily life, influencing not only clergy and nobility but also peasants and soldiers.

With the rise of merchants in the late 13th century, the need for precise time measurement became more pressing. The “Church Time” began to coexist with the “Merchants’ Time.” The adoption of sundials and early solar clocks reflected a growing need for accuracy, despite their reliance on sunlight and direct observation to be effective. The real change emerged in the 14th century with the installation of the first mechanical clocks on municipal towers and church bell towers, announcing not only the hours but also the quarter hours with chimes that echoed through the villages.

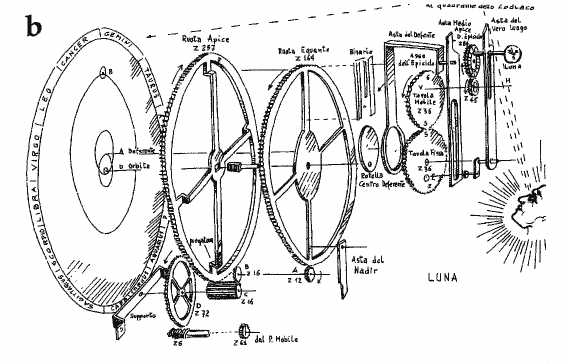

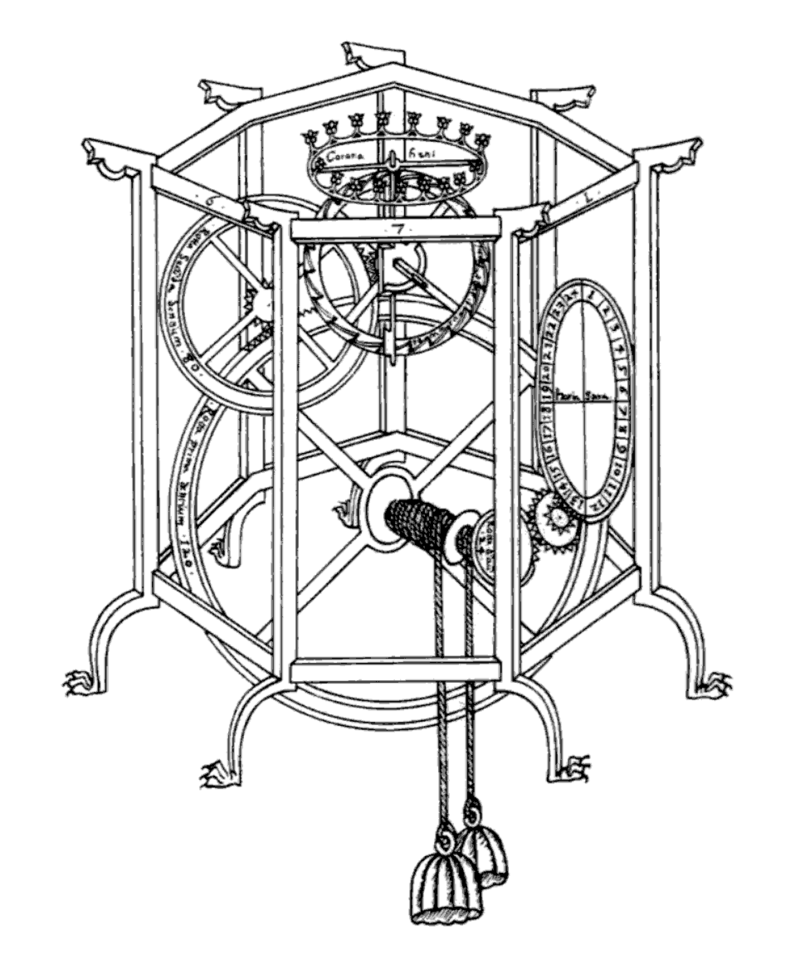

These clocks, often equipped with planetary mechanisms, were considered true marvels of technology, inspiring awe and wonder among the populace, much like we are captivated by the latest scientific achievements today. Among them stands Giovanni Dondi’s astrarium, an astronomical clock built between 1365 and 1384, capable of displaying the hour, the annual calendar, and the movement of the celestial bodies known at the time. This work, unfortunately lost, remains a symbol of the advanced astronomical and mechanical understanding of time.

The “Tractatus Astrarii,” detailed manuscripts left by Dondi, offer an immersion into his methodologies and intellectual genius and inspired the clock’s reconstruction in the 20th century. The rediscovery and reproduction of the astrarium, first in London and then in Milan, highlight the bridge between medieval ingenuity and modern curiosity, emphasizing how the roots of our digital era are deeply embedded in history.

The debate on how technology shapes society, already anticipated by Oscar Wilde when he stated that “the machine tends to make a man a machine,” finds an emblematic example in the clock, which transformed human perceptions of time from natural cycles to quantified segments, profoundly influencing our social and economic organization.

This fascinating journey through the evolution of time in the Middle Ages not only enriches our understanding of technological history but also raises questions about the ongoing impact of innovations on the fabric of human society. The history of medieval clocks is not just a chapter of the past but an ecosystem of ideas and innovations that continue to shape our future.